Antibiotic resistance is an even greater challenge in remote Indigenous communities

Antibiotic-resistant infections already cause at least700,000 deathsglobally every year.

Although the phenomenon is most concerning for serious infections people are admitted to hospital with, antibiotic resistance means common bacterial infections could one day be impossible to treat.

Appropriately, the issue has receivednationalandglobalattention in public health policy making.

But antibiotic resistance in remoteAboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communitieshas garnered minimal attention. Remote Indigenous communities are not mentioned in the currentNational Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) Strategy, for example.

It's in these parts of Australia, however, that antibiotic resistance is arguably having the most significant impact.

A key example

Antibiotics are medications used to treat bacterial infections. But when bacteria are repeatedly exposed to antibiotics, they can adapt and survive against the antibiotics previously known to kill them.

不明智地使用抗生素,例如viral infection, taking a low dose when a high dose is needed, or stopping a course of antibiotics before an infection has resolved,all contributeto antibiotic resistance.

In northern Australia, the bacteriaStaphylococcus aureus, (orS. aureusfor short, also known as golden staph) causes skin and soft tissue infections. WhenS. aureusbecomes resistant to the antibiotics commonly used to treat these infections, we call it methicillin resistantS. aureus, or MRSA.

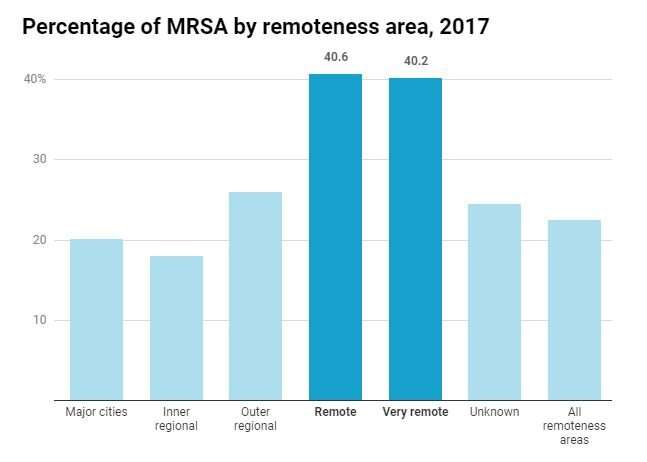

The rates of MRSA in northern Australia aresignificantly higher than elsewherein the country. Recent government figures show among people withS. aureusinfections, the rate of MRSA in remote and veryremote areaswas double that of major cities (roughly 40% versus 20%).

Australiadoesn't havea national surveillance system for monitoring rates of MRSA. So the figures can vary depending on the location, time period and the population studied.

Some studies have reported MRSA ratesclose to 60%in parts of central and northern Australia, compared toabout 13%elsewhere in Australia.

What happens when the antibiotics don't work?

Up tothree-quartersof all people in remote Indigenous communities who attend amedical cliniceach year present at some stage for treatment of a skin and soft tissue infection such as skin sores, boils or cellulitis.

The prevalence of MRSA in northern Australia means these people can no longer rely on simple,first line antibioticsfor treatment.

Treatment failure because of antibiotic resistance means skin and soft tissue infections take longer to get better, and are more likely to spread to other people.

In more serious cases, the infection can invade past the skin and cause a bone, blood or lung infection. If this happens, the patient will likely need to be flown to a hospital thousands of kilometers away.

This issue is compounded when certain antibiotics are unavailable due to shortages.

Why is antibiotic resistance so much higher in remote Indigenous communities?

The heavy burden of infections such as skin infections (as many asone in tworemote living Aboriginal children suffer from a skin infection at any one time), ear infections,pneumonia, andsexually transmitted infections, mean antibiotics need to be prescribed frequently and broadly. This allows antibiotic resistance to spread.

In addition to high levels ofinfection, underlyingsocial determinants of healthlike household crowding and poor access to facilities such as working washing machines and showers facilitate the ongoing transmission of bacteria.

Antibiotic resistance and closing the gap

Health-care workers in remote clinics come from all across Australia and New Zealand, sometimes only forshort stints. So it's important they are educated about local antibiotic resistance rates andlocal treatment guidelines.

Similarly, doctors in remote clinics need to be able to access real-time local antibiotic resistance rates. Pleasingly, an online atlas for health practitioners of antibiotic resistance rates across northern Australia, called "HOTspots", is currently being set up.

Addressingantibiotic resistancein remote Indigenous communities must be part of the ongoing effort to close the gap in health outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

Inclusion of remote Indigenous populations as a priority in theNational AMR Strategyis essential. These groups are not mentioned in the current strategy (2015-2019) but we are hopeful they will be included in the new strategy, to be released soon.

Implementing the the National AMR Strategy for remote living Indigenous Australians must be a high priority to ensureantibioticsare available to treat infections among this already vulnerable section of our population.

This article is republished fromThe Conversationunder a Creative Commons license. Read theoriginal article.![]()