More time between prostate cancer screenings could improve outcomes

A new study inJNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute, published by Oxford University Press, finds significant benefits to lengthening the amount of time between prostate cancer screenings for men.

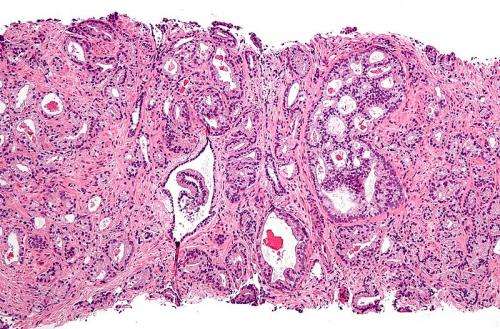

Prostatecanceris one of the most common cancers in men, affecting one in seven men over the course of his lifetime. Ablood testcalled aprostatespecific antigen (PSA) test, which measures the levels of PSA in the blood, has been used to screen forprostate cancerfor decades, because levels of PSA in thebloodcan be higher in men who have prostate cancer. But PSA levels are higher in other conditions that affect the prostate, such as certainmedical proceduresand medications, as well as an enlarged prostate or a prostate infection. Research regarding the effectiveness of such screenings in identifying and treating men with prostate cancer has so far been inconclusive.

Previous studies have shown that men with low PSA levels (<1.0 ng/mL) at ages 44 to 60 have very low risk of future prostate cancer. A study published this week inJNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Instituteby Heijnsdijk and colleagues investigated benefits and harms of screening strategies associated with lengthening the screening interval when PSA is below 1.0 ng/mL at ages 45 or 50 or discontinuing screening when PSA is below 1.0 ng/mL at age 60.

Using statistical modeling techniques, they predicted the harms (measured in tests and overdiagnoses) and benefits (measured in lives saved and life-years gained) of PSA-stratified screening strategies versus the traditionally recommended screening for men between 45 and 69 every other year.

The models projected that screening 10,000 men ages 45 to 69 every other year would require more than 110,000 screens and result in up to 348 overdiagnoses. They found that lengthening the screening interval from two to eight years would result in a decrease of overdiagnosis by 5- 24%, and only 3.1 to 3.8% fewer lives saved.

此外discontinui的模型预测ng screening at age 60 for everyone would greatly reduce overdiagnoses (by 79-82%) but would save substantially fewer lives compared to screening until age 69.

"This study shows the power of comparative modeling: by using two models with different underlying assumptions, we can identify uncertainty around the outcomes," said lead author Eveline Heijnsdijk, Ph.D.

User comments